Image credit: Pexels

Artificial intelligence is steadily transforming the way organizations find and evaluate talent. From automated resume screening to large-scale sourcing of passive candidates, AI systems offer efficiency, scalability, and speed that traditional hiring workflows could never match. As adoption accelerates, however, concerns around fairness, accountability, and embedded bias have moved to the forefront.

The challenge is no longer whether AI belongs in recruitment. The real question is how organizations use it responsibly, without outsourcing judgment, ethics, or accountability to systems that were never designed to carry moral weight.

Where Bias Begins

For years, traditional Applicant Tracking Systems relied heavily on keyword matching. Candidates who knew how to optimize resumes for machines were rewarded, while equally qualified applicants were filtered out for lacking the right phrasing. That approach quietly introduced bias long before AI entered the conversation, favoring system literacy over substance.

AI systems introduce a different but equally consequential risk. When models are trained on historical hiring data, they inherit the preferences, assumptions, and blind spots embedded in past decisions. If previous hiring patterns favored certain schools, companies, titles, or demographics, AI can unintentionally amplify those biases at scale.

Shawn Jahromi, board advisor at Alpharay Consulting and a doctoral researcher in digital transformation, cautions against assuming neutrality simply because decisions are automated.

“AI is a piece of code that sees patterns,” Jahromi explains. “It doesn’t have a moral compass. Whatever bias exists in the data is going to show up in the output.”

From Jahromi’s standpoint, the danger is not malicious intent, but misplaced trust. Algorithms are frequently treated as arbiters rather than tools, even though they are trained on datasets shaped by historical inequities, uneven access to education, and culturally narrow definitions of success.

He points out that bias can enter systems long before an employer ever deploys a hiring tool. Data vendors, résumé databases, and training sets are rarely interrogated for representativeness. “If your system is trained on resumes from a narrow segment of society,” he says, “then your definition of ‘qualified’ quietly becomes exclusionary.”

Jahromi is particularly concerned with accountability gaps. Unlike human decision-makers, AI systems cannot be held morally or legally responsible for outcomes. “If a hiring decision leads to discrimination, who is accountable?” he asks. “The software? The vendor? Or the organization that deployed it without governance?”

This question sits at the core of his critique. Without clear ownership and oversight, AI risks becoming a convenient shield for organizations seeking efficiency without scrutiny.

An Effort to Reduce Bias at the First Touchpoint

One of the most overlooked sources of bias occurs before candidates are ever evaluated: sourcing. Pankaj Khurana, VP of Technology and Consulting at Rocket, has spent more than 20 years hiring across startups and Fortune 500 organizations. His experience led him to a consistent observation. Much of hiring bias happens at the very first step, when recruiters interpret job descriptions and decide who to search for.

To address this, Khurana developed Firki, a Chrome extension that converts job descriptions into unbiased Boolean search strings. Rather than relying on a recruiter’s subjective interpretation or recent hiring experiences, Firki standardizes sourcing logic from the outset.

“I wanted to reduce the perception of bias,” Khurana says. “None of my clients or my team is biased toward any hire. We hire purely based on merit. But perception matters. If candidates never hear back, they assume bias, even when the issue is fit.”

By removing human assumptions from the initial search phase, Firki widens the candidate pool instead of narrowing it prematurely. Recruiters retain discretion later in the process, but the early-stage gatekeeping becomes more consistent and explainable.

Khurana is also realistic about AI’s limits. He does not believe hiring can ever be perfectly fair. What he believes is achievable is a system that is more transparent, more accountable, and less dependent on gut instinct.

“AI will help us hire more fairly than before,” he says. “Not perfectly. But better.”

The Shift From Keywords to Context

While Firki focuses on neutralizing bias at the sourcing stage, Recruitment Intelligence tackles a different problem: how candidates are evaluated once they are found.

Founded by Gregg Podalsky, Recruitment Intelligence assigns candidates a score from one to ten based on contextual fit rather than binary keyword matching. Podalsky has been in recruiting since the late 1990s, long before online job boards became dominant, and that historical perspective shapes his approach.

“The information AI analyzes is only as good as the information it takes in,” Podalsky explains. “If you treat resumes as static documents, you miss what people actually know how to do.”

Rather than disqualifying candidates for missing one requirement, the platform adjusts scores to reflect partial matches and transferable experience. Someone with four years of experience instead of five is not excluded, but scored differently and surfaced for review.

“Our platform looks at context, not just text,” Podalsky says. “A cruise line procurement officer understands supply chains, even if those words aren’t explicitly on the resume.”

This approach intentionally avoids hard cutoffs that historically eliminated strong candidates for minor gaps. It also mirrors how experienced recruiters think, evaluating capability in gradients rather than absolutes.

Human Judgment Still Matters

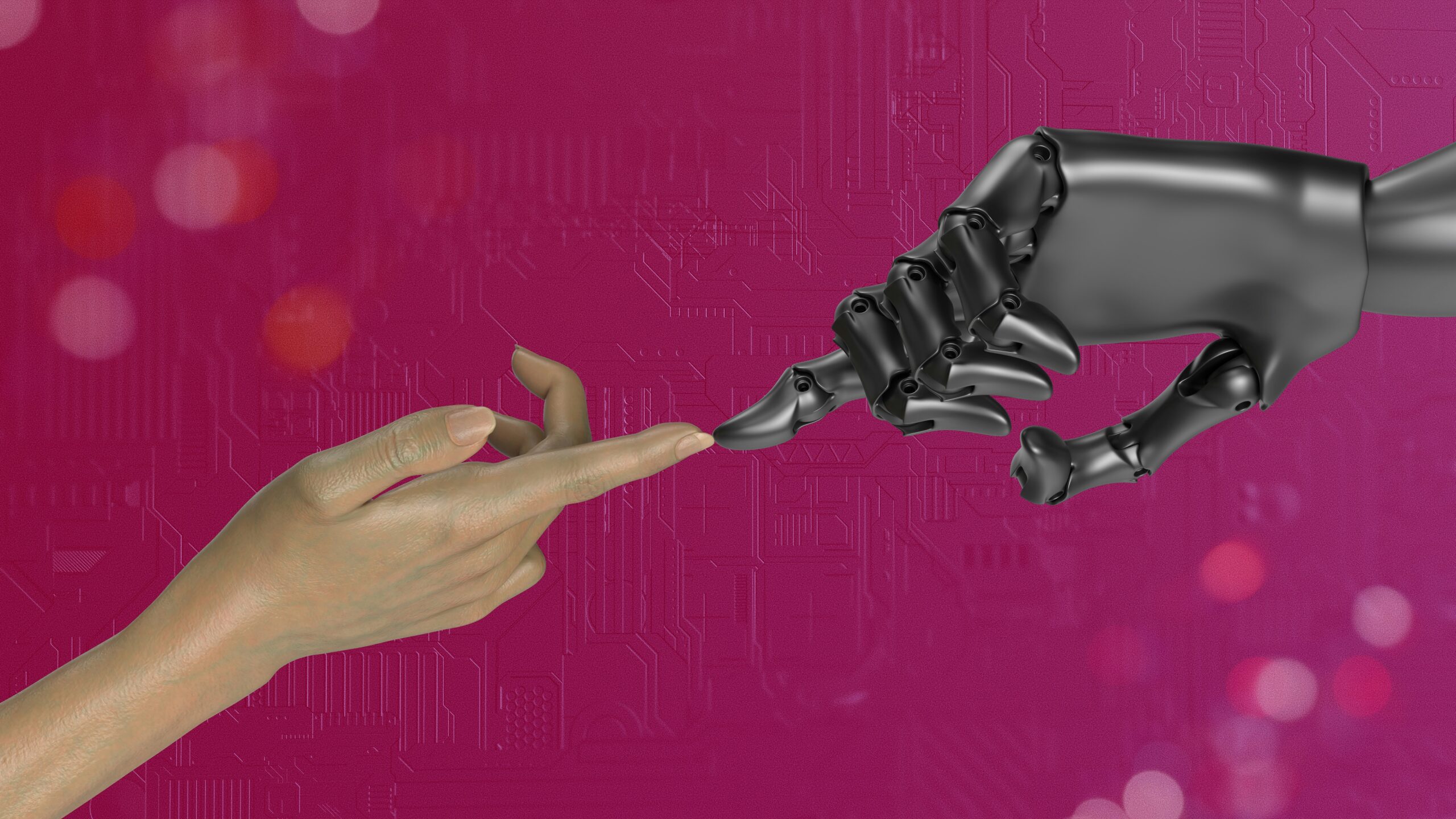

Despite advances in contextual inference and large-scale automation, all three leaders agree on a hard boundary. AI cannot evaluate ethics, communication, accountability, or judgment under pressure.

Podalsky points to soft skills as a decisive example. “The way someone communicates, explains a concept, or bridges technical and non-technical teams can’t be measured on a resume,” he says. “You need experienced humans to assess that.”

Jahromi frames the issue more bluntly. “You can’t blame AI for a decision that leads to a lawsuit,” he says. “At the end of the day, accountability still falls on people.”

This is where the “human in the loop” model becomes essential. Human oversight allows for audit trails, spot checks, and ethical review. Without it, organizations risk treating algorithmic outputs as unquestionable simply because they are automated.

Balancing Innovation With Accountability

AI will continue to transform hiring processes; its long-term adoption depends on organizations’ responsible use. Smarter algorithms can enhance efficiency and identify the right talent, but fairness in recruitment will always rely on the people who design, deploy, and supervise these systems.