Image credit: Pixabay

Artificial intelligence is reshaping the modern workplace at a pace most organizations are not structurally prepared to handle. Boards and executives are racing to deploy AI tools in pursuit of efficiency gains, cost savings, and competitive advantage. Yet many of these efforts stall or disappoint. The reason is not technological immaturity. It is organizational denial.

AI is being layered onto systems that were never designed for the way work actually happens today. Without confronting that reality, companies risk automating dysfunction rather than transforming it.

As Oksana Lukash, a four-time Chief People Officer who has led HR organizations in highly regulated and high-growth environments, puts it bluntly, “We keep layering AI on broken and outdated processes and then are surprised when it doesn’t change anything. That’s not innovation. That’s insanity.”

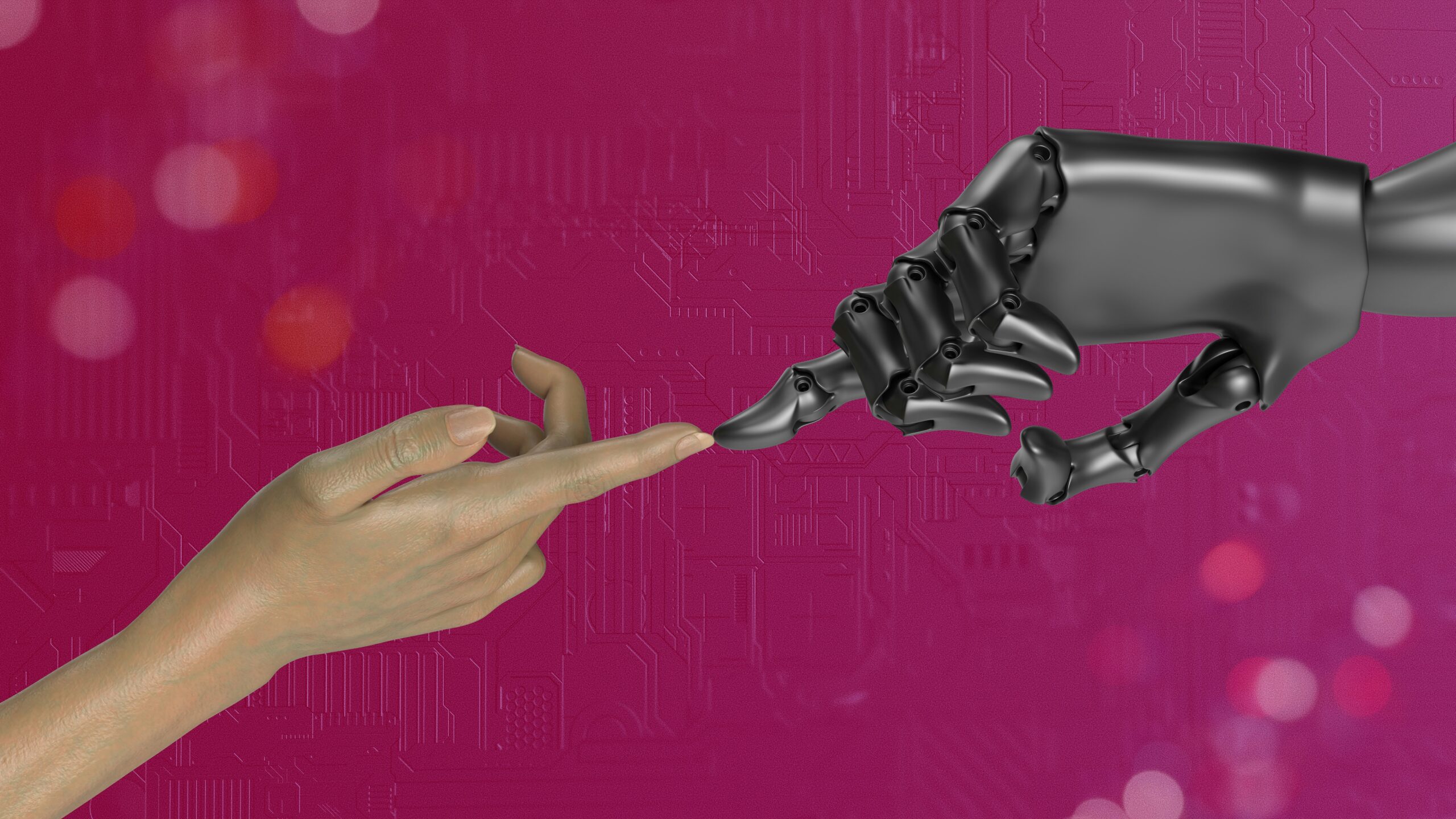

What is emerging instead is a growing consensus that successful AI integration must begin with people, not platforms.

Outdated Structures Are Holding AI Back

Much of the modern workplace still runs on assumptions forged more than a century ago. Fixed schedules, rigid hierarchies, narrowly defined roles, and compliance-first processes were built for an industrial economy, not a knowledge economy augmented by intelligent systems.

Lukash argues that this disconnect is one of the biggest barriers to meaningful AI adoption. “The way companies work was built by people, for people, for a world that no longer exists,” she says. “The nine-to-five workday came from Henry Ford. We’re still operating inside frameworks that are decades old.”

When AI is introduced into these legacy structures without rethinking how work should be done, it tends to reinforce inefficiencies rather than eliminate them. Automation accelerates tasks that may not matter, while deeper organizational friction remains untouched.

The result is predictable: leadership expects transformation, employees experience disruption, and trust erodes in the gap between promise and reality.

Trust First, Then Tech

For organizations serious about integrating AI responsibly, trust is not a soft concept. It is a prerequisite.

Employees who do not understand how AI will be used, or who fear it will quietly replace them, are unlikely to engage honestly in the process. Lukash has seen this dynamic repeatedly. “If people think that being transparent about what they do is just a way for the company to automate their role away, they’re not going to tell you the truth,” she explains.

This is especially true for frontline and individual contributor roles, where financial precarity and job insecurity are most acute. Without open communication and psychological safety, AI initiatives can quickly feel extractive rather than empowering.

Lukash emphasizes that leaders must address fear directly. “Is AI going to replace some jobs? Absolutely,” she says. “But it’s also going to create new ones, just like every major technological shift before it. The problem is when companies don’t own that message.”

Transparency, she argues, is not about reassuring people with platitudes. It is about involving them early, explaining trade-offs honestly, and treating AI adoption as a shared organizational challenge rather than a top-down mandate.

Efficiency Versus Capacity

One of the most common mistakes leaders make with AI is framing its value purely in terms of efficiency. Faster workflows, leaner teams, higher output. While these gains are real, Lukash believes they are also incomplete.

“Efficiency is about doing broken tasks faster,” she says. “Capacity is about freeing up time so people can do work that actually matters.”

That distinction reframes the role AI should play inside organizations. Instead of squeezing more productivity out of employees, AI can be used to eliminate low-value tasks altogether, creating space for judgment, creativity, and human connection.

This shift matters because it changes how employees experience AI. Capacity-building tools feel additive rather than punitive. They expand what people can contribute instead of narrowing their roles.

In Lukash’s view, organizations that focus exclusively on efficiency miss the larger opportunity. “AI should give people time back,” she says. “Time to think, to collaborate, to build relationships. That’s where real value comes from.”

Empowering Employees to Lead Innovation

The most successful AI initiatives often come from unexpected places. Lukash points to an example from apparel brand Good American, where leadership invited teams across the company to experiment with AI and propose solutions to real business problems.

There were no rigid rules or prescribed use cases. Employees were simply given space, time, and permission to explore.

“The assumption was that marketing or customer service would win,” Lukash recalls. “Instead, it was the accounting team.”

That team identified a painful returns and chargebacks process and built an AI-supported solution that ultimately saved the company over $100,000. The lesson was not about technology. It was about proximity to the work.

“People closest to the problems usually understand them best,” Lukash says. “If you give them tools and trust them to figure it out, they will surprise you.”

This approach reframes employees from passive recipients of AI tools into active co-creators. It also signals respect, reinforcing the trust required for long-term adoption.

Rethinking Roles and Leadership Development

A human-centric approach to AI also demands a more nuanced view of talent. Blanket policies and standardized career paths are increasingly misaligned with how people actually contribute.

Lukash refers to this as the “peanut butter approach” to management. “We spread the same expectations and policies across everyone and wonder why it doesn’t work,” she says. “People have different strengths, different zones of genius.”

AI creates an opportunity to redesign roles around those strengths, rather than forcing high performers into management tracks that may not suit them. Too often, organizations reward exceptional individual contributors by promoting them into leadership without preparing them or even asking if that path is desirable.

“Leadership is about making other people better,” Lukash notes. “It’s not about personal achievement. And not everyone wants that role.”

By offering real-world exposure, flexible career paths, and equal prestige for individual contributors, companies can build leadership pipelines that are both more humane and more effective.

Final Thoughts

AI will not fix broken workplaces on its own. But it can expose what no longer works and create momentum for change.

Organizations that succeed will be those willing to rethink outdated structures, prioritize trust over speed, and treat employees as partners in transformation. As Lukash puts it, “It has to be human and AI, not AI plus human. You can’t take humanity out of work and expect it to get better.”

For leaders navigating the next phase of AI adoption, the challenge is clear. The question is not how fast you can deploy new tools, but whether you are building an organization worthy of them.